Big Context Windows Are a Big Deal

Last week, I got my hands on Google’s newest generative model: Gemini 1.5, a multi-modal behemoth that can consume up to an hour of video, 11 hours of audio, 30,000 lines of code, or 700,000 words. That’s a big leap forward in terms of context length: Gemini accepts 5x times more input than its beefiest predecessor, Claude 2.1.

I’ve been excitedly anticipating the era of long context windows for a while, not just because they enable generative models to solve entirely new kinds of problems, but also because they just might transform the way we develop with LLMs. But I’m getting ahead of myself. First, let me share with you some of my favorite Gemini 1.5 experiments.

Prompting with Video

AI Family Video Archive 2.0

Back in the stone ages, i.e. 2020, I devoted a month of my life building an AI-powered family video archive. The idea was to use machine learning (image recognition, speech-to-text, embeddings, etc) to create what was essentially Google Search but for my personal family video archive. It worked, but there was a flaw between chair and keyboard: I didn’t know what to search for. So many hours of video, from so long ago! What precious family moments had I entirely forgotten about, or was too young to form memories of in the first place?

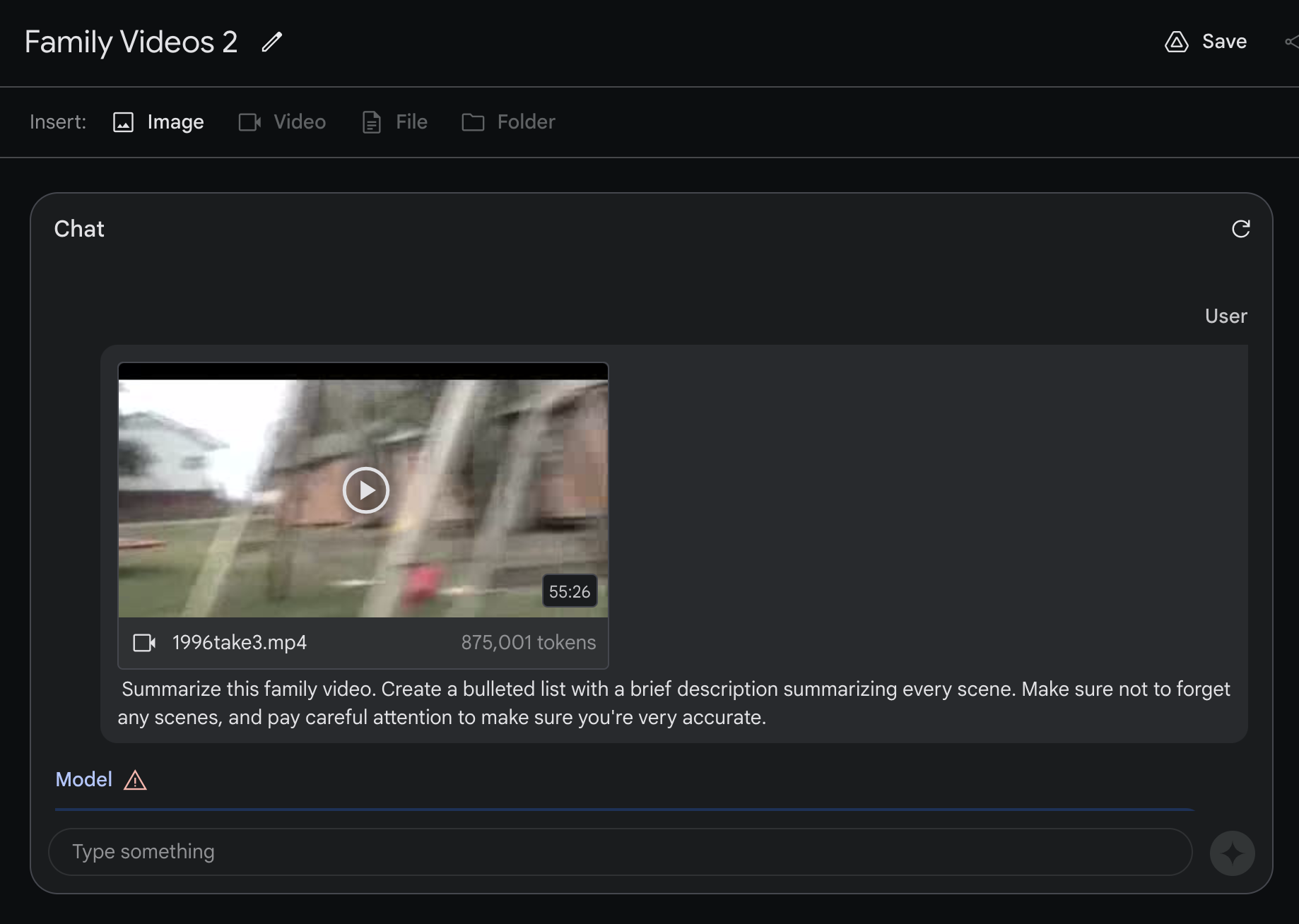

Enter Gemini 1.5. One of the very first thing I uploaded to this bad boy was a one-hour family video from 1996. Unlike my original AI archive that took a month to build, this experiment took only a few minutes to set up, and most of that time was spent downloading and converting the video into the right format. I uploaded my family video to Google Drive, inserted it into the prompt, then added the instruction text:

Summarize this family video. Create a bulleted list with a brief

description summarizing every scene. Make sure not to forget any scenes,

and pay careful attention to make sure you're very accurate.

And it worked!

Mostly. All of these scenes are indeed clips from my video, and in the correct order. Gemini did miss a scene or two, which is why I packed my prompt with clarifiers like: “Make sure not to forget any scenes.” Overall, I was impressed. The chances of me watching this hour-long video end-to-end were nil, so it was nice to have Gemini give me the highlight reel.

AI Gardener

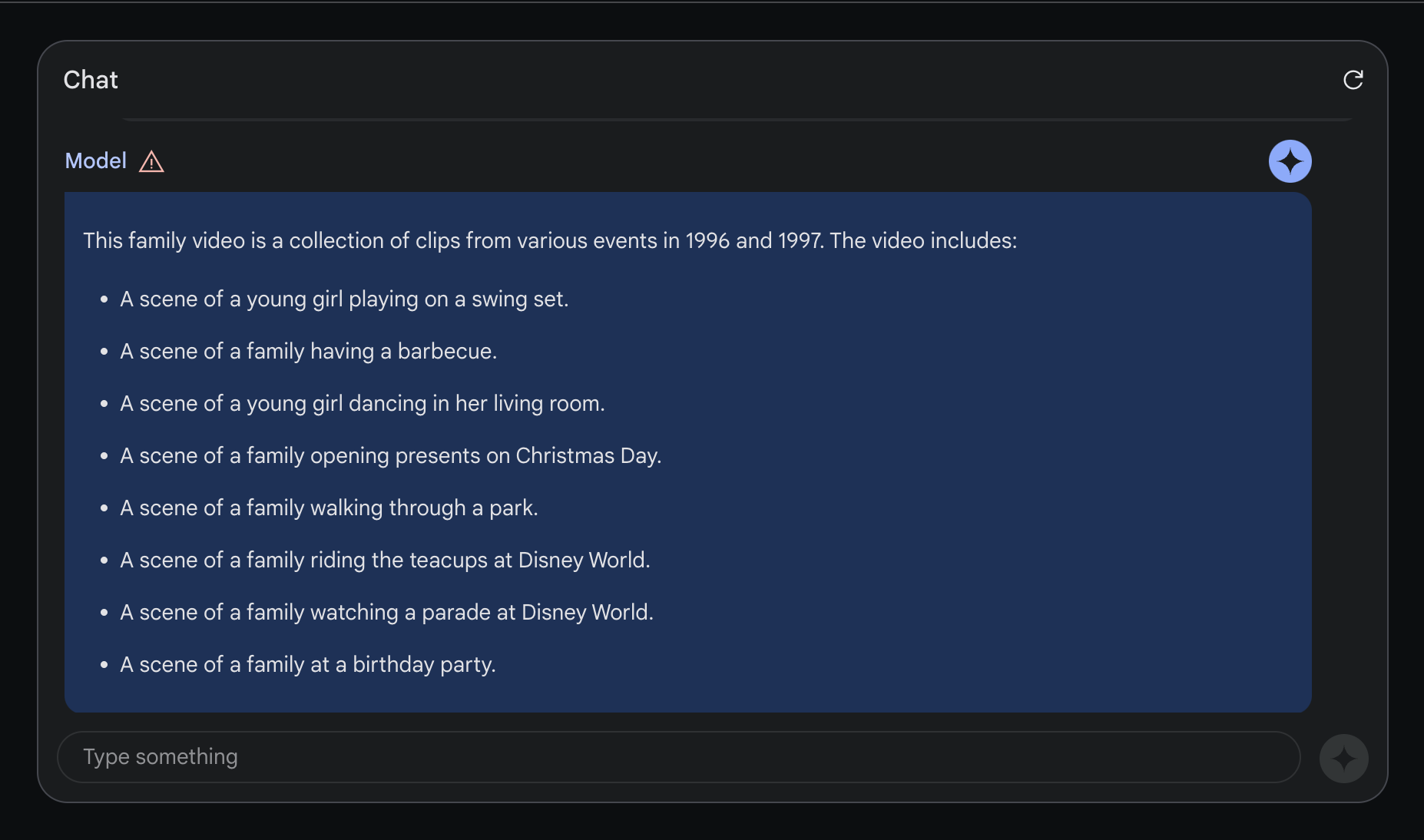

If you’re a developer, you may occasionally be overcome with crippling insecurity when tasked with doing anything in the physical world, i.e. meatspace. At least, this was how I felt when I moved into a new house that came with a lawn. I don’t know the first thing about landscaping. Keeping living organisms alive? Not really my area of expertise. Gemini 1.5 to the rescue?

My next experiment was to take a phone recording of my lawn and ask Gemini 1.5 to tell me how to handle it:

Here’s what Gemini 1.5 had to say. (I’ve added asterisks around the interesting bits.)

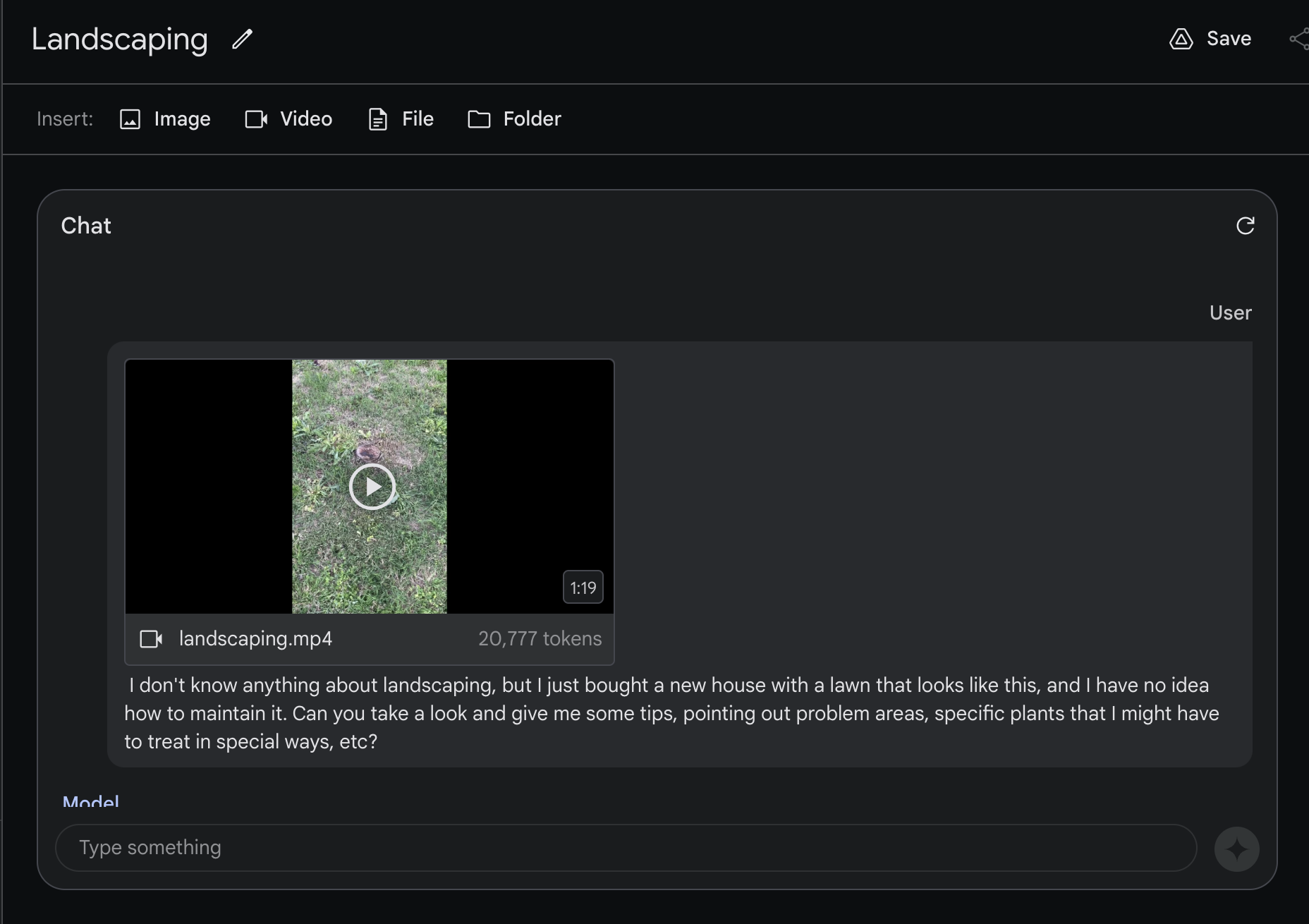

The landscaping in the video features a variety of plants, including:

**St. Augustine grass: This is a warm-season grass that is popular in Texas. It is relatively low-maintenance, but it does need to be watered regularly and fertilized occasionally.**

**Agave**: This is a succulent plant that is native to Mexico and the southwestern United States. It is very drought-tolerant and does not need to be watered often.

**Yucca**: This is another succulent plant that is native to the southwestern United States. It is also very drought-tolerant and does not need to be watered often.

Dandelions: These are weeds that can be difficult to control. They can be removed by hand or with a herbicide.

Overall, the landscaping is in good condition. However, there are a few problems that I see:

Weeds: There are a few weeds growing in the grass and in the gravel. These can be removed by hand or with a herbicide.

Dead leaves: There are some dead leaves on the ground. These should be raked up and removed.

**Broken planter**: There is a broken planter in the yard. This should be removed and replaced.

Here are some specific tips on maintaining the landscaping:

Water the grass regularly: St. Augustine grass needs to be watered deeply and infrequently. Water it once or twice a week, depending on the weather.

Fertilize the grass occasionally: St. Augustine grass should be fertilized once or twice a year. Use a fertilizer that is specifically designed for St. Augustine grass.

Remove weeds: Weeds can be removed by hand or with a herbicide. Be sure to use a herbicide that is safe for St. Augustine grass.

Rake up dead leaves: Dead leaves should be raked up and removed. This will help to prevent the spread of disease.

Trim the agave and yucca: Agave and yucca should be trimmed occasionally to remove dead leaves.

In addition to the problems that I mentioned above, there are a few other things that you might want to consider:

Mulch: Mulch can help to retain moisture and suppress weeds. You might want to consider adding mulch to the gravel areas.

Edging: Edging can help to create a clean line between the grass and the gravel. You might want to consider adding edging to the landscaping.

Lighting: Lighting can help to highlight the landscaping and make it more inviting. You might want to consider adding lighting to the yard.

Though I’m no gardener, I’m pretty sure Gemini was on the money here. It correctly identified my agave, yucca, and the profusion of dandelions/weeds, as well as a broken planter the former resident left behind. I was particularly impressed/weirded out by this line: “St. Augustine grass: This is a warm-season grass that is popular in Texas.” It would seem that Gemini figured out where I lived by identifying my grass? Weird! But… useful?

Improving My Tennis Serve

My final experiment with video was another throwback to an AI project I’d built back in olden times: a program for using pose-tracking to analyze and improve my tennis serve. Even in the era of generative AI, simple pose-tracking models are a useful and accurate technique for analyzing human motion. But because it was so easy, I decided to throw some clips of my tennis serve into Gemini 1.5 and see if it had any suggestions for improvement:

Is Gemini being overly generous when it says, “Your serve looks good!”? Probably yes. But still, it was definitely on point about the fact that I can’t toss the ball consistently. And no one ever once told me I need to improve my “leg drive.”

The Era of Document Prompting

Video is flashy and all, but in this developer’s opinion, prompting with ~700,000 words of text is just as impressive. If 700,000 words sounds a little vague, here’s a quick reference:

| Document | Word Count |

|-------------------------------------------|------------|

| The US Constitution | 4,543 |

| Introduction to Algorithms Textbook | 328,000 |

| War and Peace | 587,000 |

| The King James Bible | 783,137 |

| The Complete Harry Potter Book Series | 1,084,170 |

(Note: Counts are approximate)

We can finally throw entire novels, textbooks, and reference manuals into prompts. Not to mention, we can stop wasting so much time and energy thinking up clever ways to stuff additional info into our prompts, and building out complicated engineering solutions (like RAG) to augment the data our models have access to.

What does that mean? More people (i.e. non-coders) can prototype more complex applications faster. Welcome to the era of document prompting.

Prompting with Manuals

In the past, if we wanted to teach an LLM to do a task, we had two prompting techniques at our disposal:

- Instruction prompting: Describe the task we want completed in a few sentences.

- Example prompting: Feed the model input-out examples (i.e. for translation, example pairs of sentences in English and their French translations). If we had large example sets (i.e. thousands), we could use the to tune a model. Smaller example sets could be used for few-shot prompting.

Unfortunately, not all problems could be solved with these two methods. Take translating low-resource languages . For as long as I’ve been working in NLP, the problem of translating languages spoken by only a few people has been nigh impossible. With long context windows, no longer. In their report on Gemini 1.5, DeepMind showed it could be done by writing a prompt that enabled Gemini to translate from English to Kalamang, a language with fewer than 200 speakers. They did it by prompting Gemini with:

- 500 pages of linguistic documentation (i.e. akin to a Kalamang textbook)

- a dictionary

- ≈ 400 parallel sentences

This result blew me away, not only because it’s so cool in its own right, but also because it got me thinking: what new abilities are unlocked when we start prompting models with textbooks? Or guides? Or manuals?

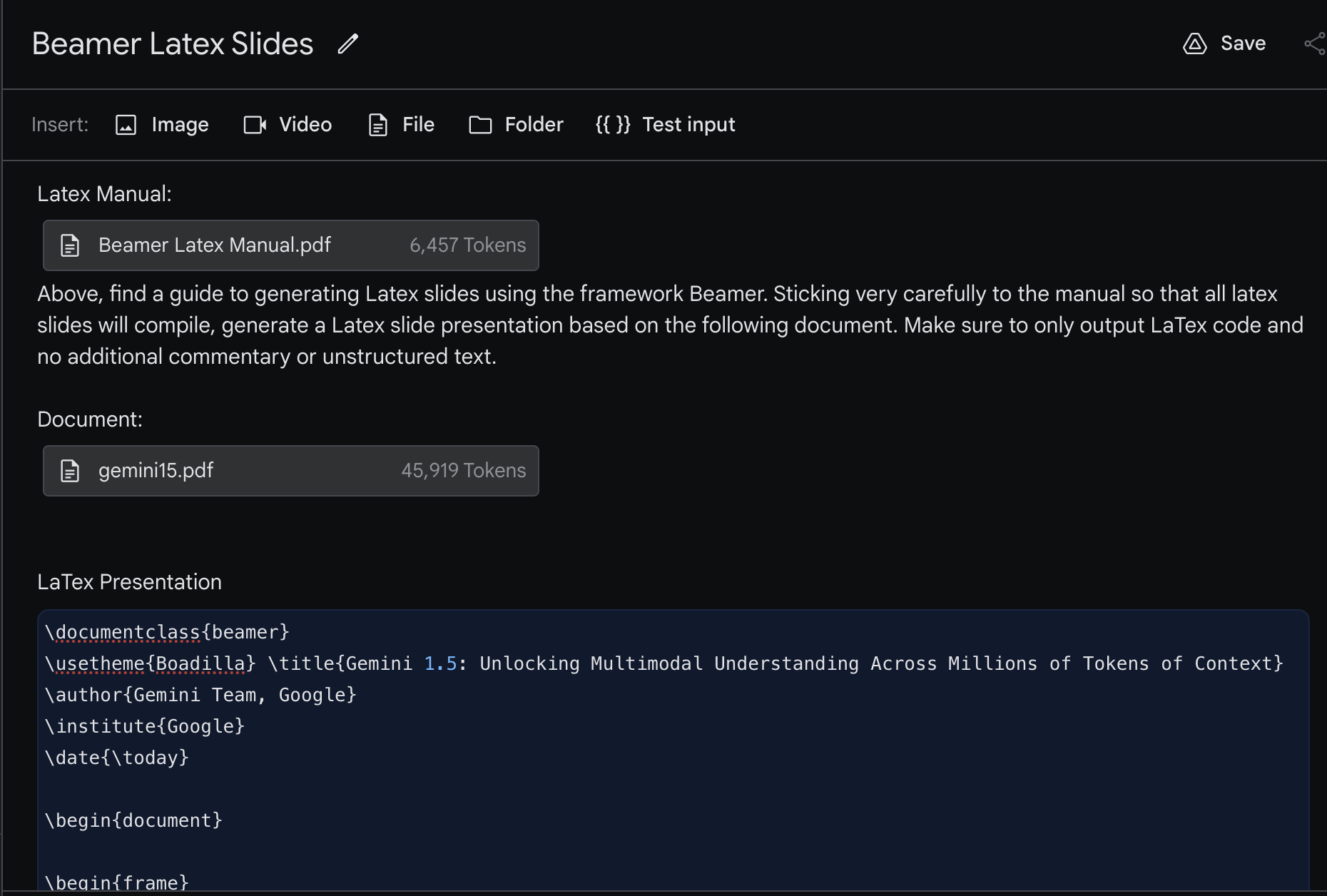

LaTeX Slide Generator

I decided to apply this approach–“textbook prompting”–to a problem I’ve been grappling with for some time–figuring out a way to automate my least favorite task: making slides. I would love to be able to feed an LLM one of my blog posts and have it transform the post into a slide presentation. Alas, I’ve had little luck. You might think image generation models like DALLE would be able to help here, but no: image generation models still suck at generating lucid text.

Instead, I decided to turn to LaTeX. For the uninitiated, LaTeX is a markup language for formatting documents and slide presentations. It enables scientists, mathematicians, and researchers to write beautifully formatted research papers and presentations with perfectly rendered tables, graphs, and mathematical equations–that is, if they can get their LaTeX code to compile before they rage quit.

Since generative models have proven effective at generating code, I wondered if I could use them to help me generate LaTeX slides. I wanted to write a prompt that could:

- Read a blog post

- Spit out a LaTeX presentation version of that blog post

Unfortunately, modern LLMs seem almost as baffled by LaTeX as I am; they’d always generate LaTeX with too many errors to compile.

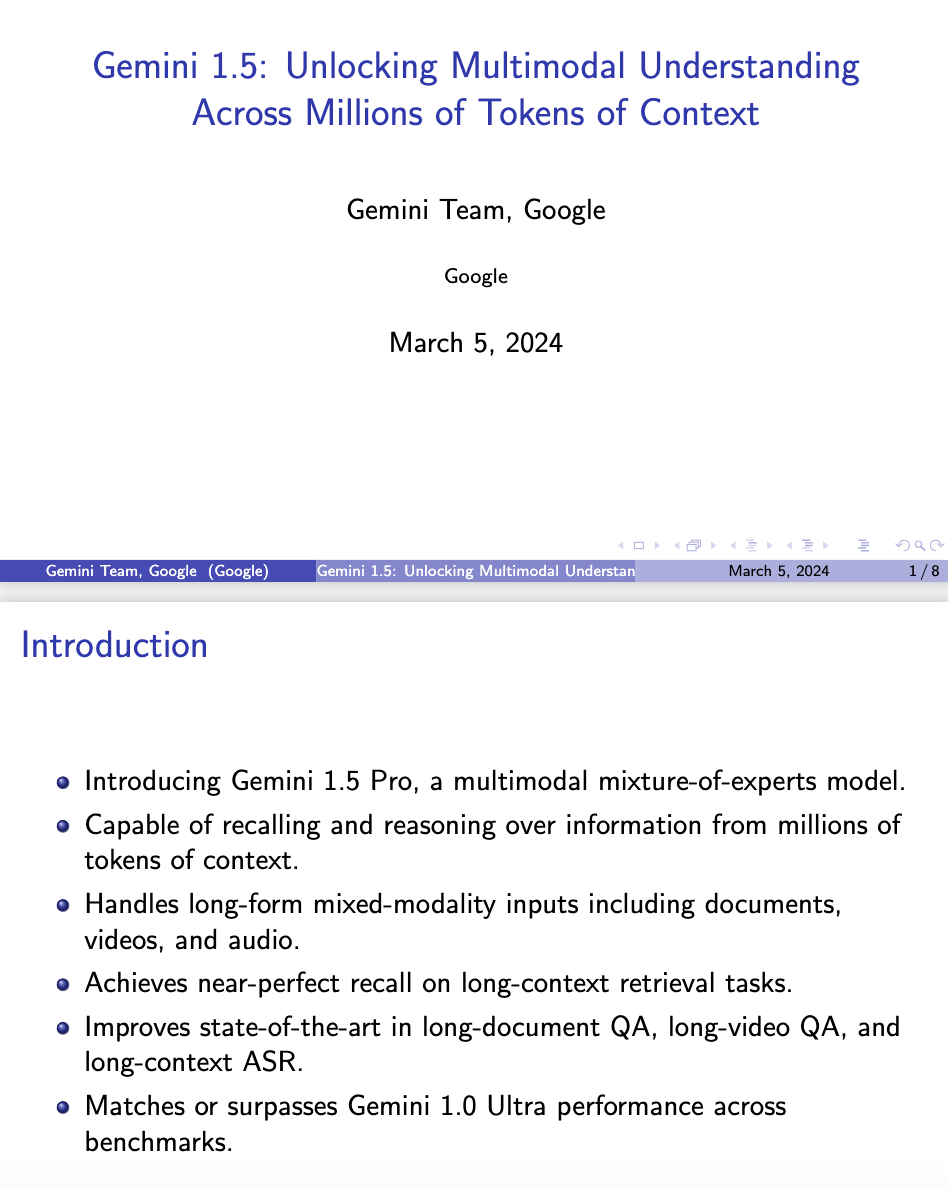

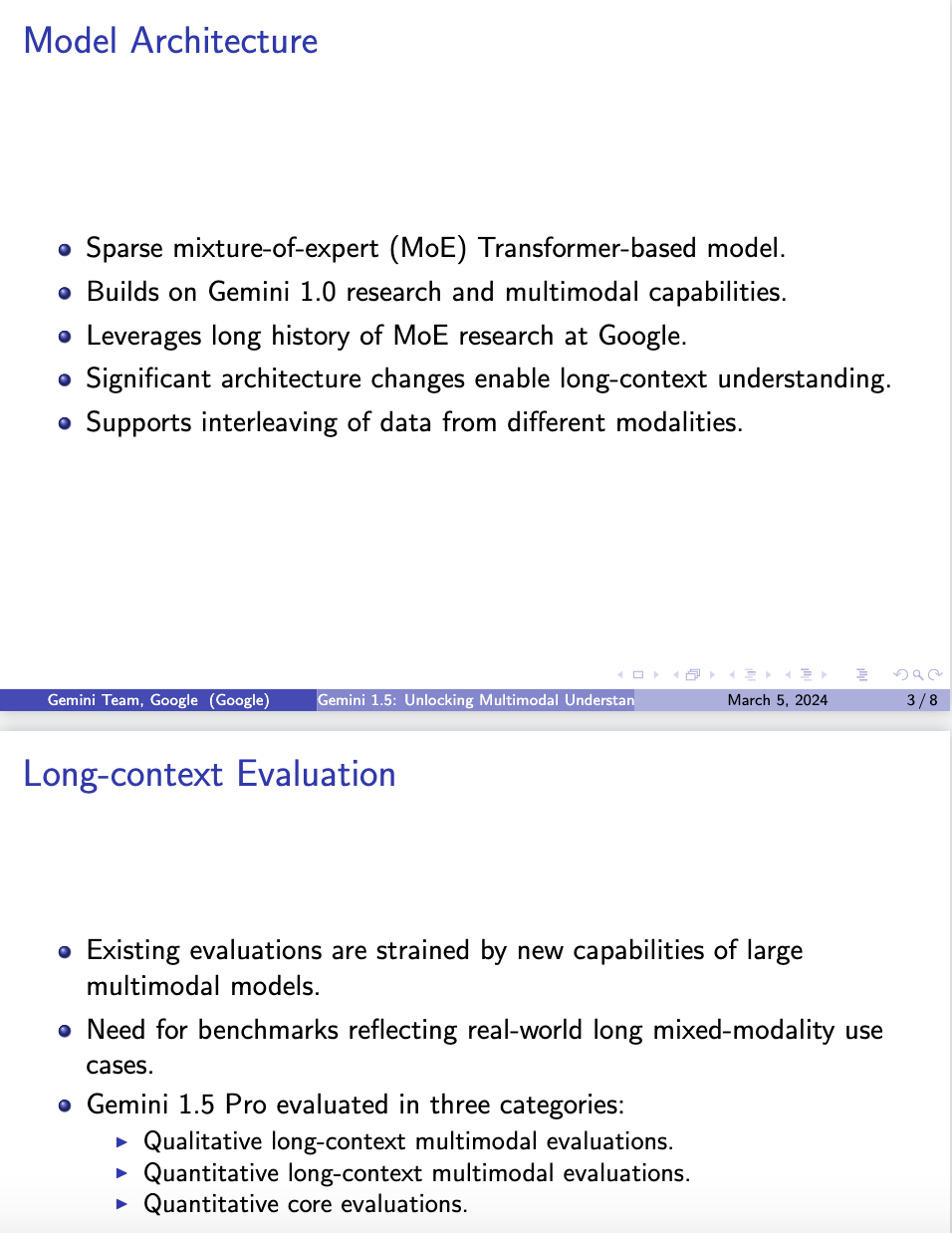

With Gemini 1.5, I tried something new, inspired by the DeepMind authors: prompting the model with a series of LaTeX/Beamer tutorial blog posts, i.e. “textbook prompting.” And it worked:

I prompted Gemini with a couple of LaTeX blog posts in the form of a PDF, then sent it a second PDF–in this case, the DeepMind Gemini 1.5 Research paper–and asked it to turn the latter into a slide presentation. Gemini output functional LaTeX code I was able to compile into this deck:

I mean, is there any surer mark of genius than mastering LaTeX?

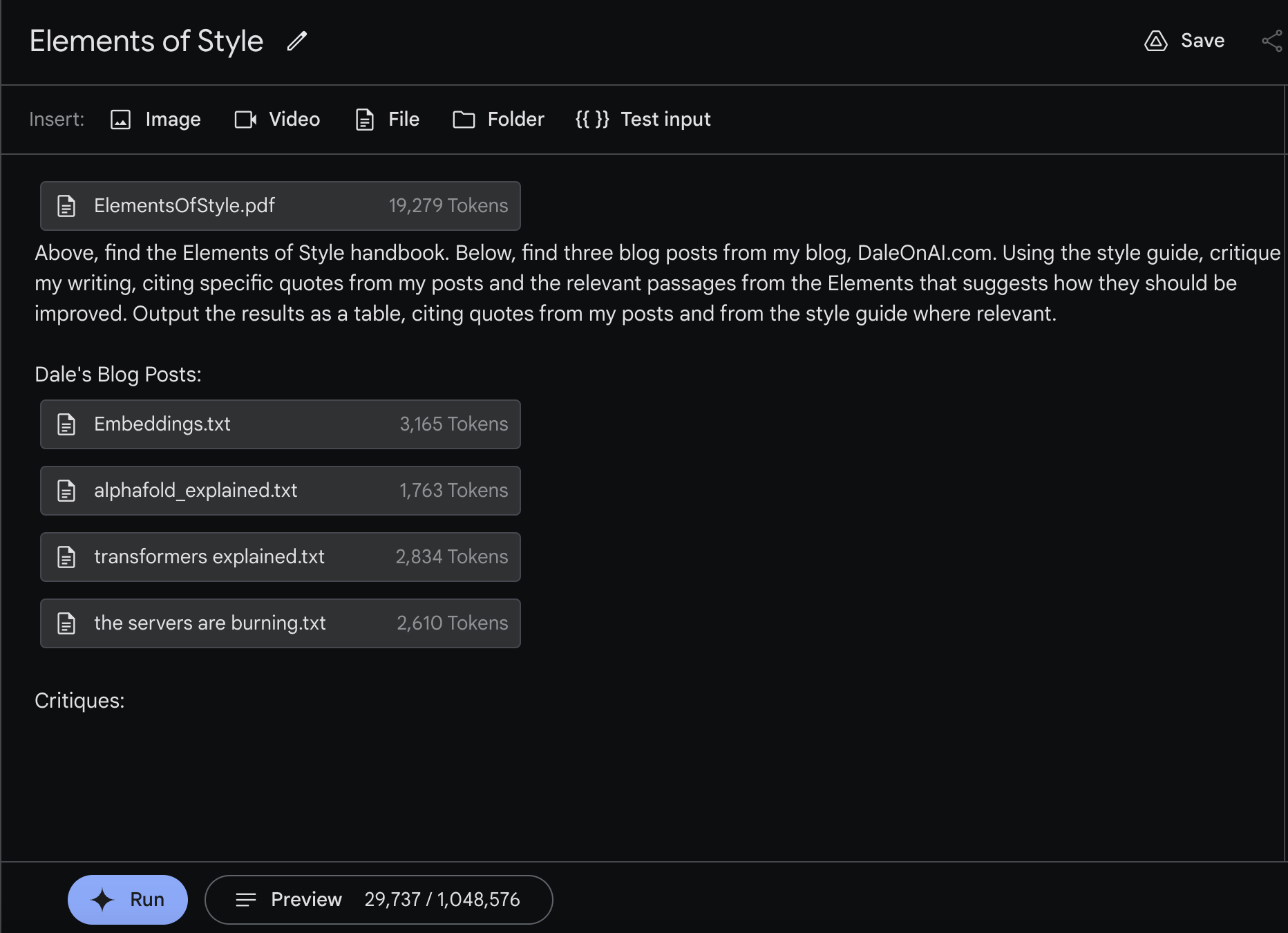

Writing With Style

Another thing generative models are strangely bad at? Writing well. It’s a bit of a mystery, but whenever I’ve asked an LLM to critique my writing style or improve a paragraph, I’ve always found its output to be unconscionably corny. LLMs seem not to understand a cardinal rule of writing: show don’t tell. They’re about as nuanced as a slap in the face, and their propensity for puns is just repulsive. With this in mind, I wondered if I could make Gemini 1.5 a better writing partner by prompting it to improve my daleonai.com blog posts by prompting the model first with William Strunk’s famous The Elements of Style.

I can definitely say that the style guide made Gemini a much better critiquer:

| Dale Quote | EoS Rule | Suggested Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| "Embeddings are one of the most versatile techniques in machine learning, and a critical tool every ML engineer should have in their tool belt. It’s a shame, then, that so few of us understand what they are and what they’re good for!" | Rule 11: Put statements in positive form. | "Embeddings are a powerful and versatile technique in machine learning, essential for any ML engineer's toolkit. Understanding their potential unlocks a wide range of applications." |

| "With Word2Vec, similar words cluster together in space—so the vector/point representing “king” and “queen” and “prince” will all cluster nearby. Same thing with synonyms (“walked,” “strolled,” “jogged”)." | Rule 13: Omit needless words. | "Word2Vec positions similar words like "king," "queen," and "prince" close together in the embedding space. Synonyms such as "walked," "strolled," and "jogged" also cluster together." |

| "The Universal Sentence Encoder model has tons of uses, especially when it comes to text search. That’s because USE embeddings capture sentence meanings rather than overfitting on individual words." | Rule 12: Use definite, specific, concrete language. | "The Universal Sentence Encoder excels in text search applications. Its embeddings effectively capture the semantic meaning of sentences, going beyond mere word overlap." |

| "So the first step is to determine how similar two amino acid sequences are. To do that, biologists typically compute something called an MSA or Multiple Sequence Alignment." | Rule 17: In summaries, keep to one tense. | "The initial step involves assessing the similarity between two amino acid sequences. Biologists typically achieve this through Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA)." |

| "BERT proved that you could build very good language models trained on unlabeled data, like text scraped from Wikipedia and Reddit, and that these large “base” models could then be adapted with domain-specific data to lots of different use cases." | Rule 14: Avoid a succession of loose sentences. | "BERT demonstrated the feasibility of constructing high-quality language models from vast amounts of unlabeled data, such as text extracted from Wikipedia and Reddit. These foundational models can then be fine-tuned with domain-specific data to address a wide range of applications." |

It was able to accurately quote rules and their numbers from the Elements of Style PDF. Pretty neat!

Kitchen Sink Prompting

On the topic of blog posts: you better believe that one of the first things I tried to do with Gemini 1.5 was get it to generate this entire blog post for me. To accomplish that, I set out to engineer a mega-prompt. In Google docs, I started assembling everything I thought could possibly relevant to generating a blog post into one giant document. The first page looked like this:

My document prompt consisted of:

- A table of contents, describing each section of the Google Doc

- A description of the task, i.e. “Your job is to write blog posts in the style of Dale Markowitz,” along with the potential title of said post.

- A ramble-y, stream-of-consciousness summary of the blog post I recorded on my phone while on a long walk. (Side bar, this is another one of my favorite LLM use cases: going on long walks, blabbing into my phone’s recorder, than using an LLM to transform the whole thing into an eloquent memo.)

- Some sample posts from my blog daleonai.com, with an instruction to read them for style

- Reference resources, including the DeepMind research paper, Google’s launch blog post, and some use cases culled from Twitter/X

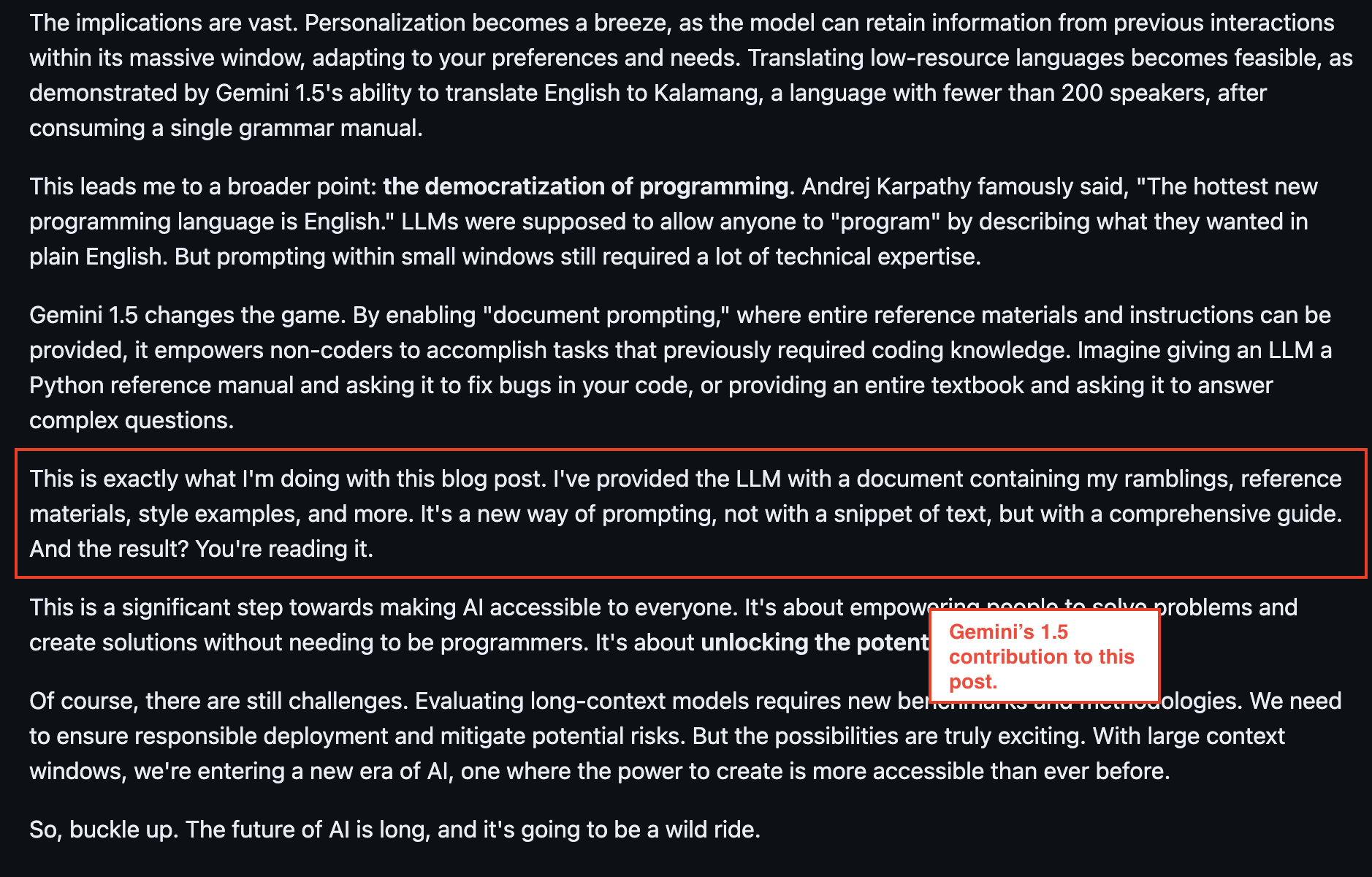

In other words, I threw everything but the kitchen sink into my massive document prompt, which is why I’m going to call this technique “kitchen sink prompting.” The final prompt document was around 70,000 tokens–just a fraction of Gemini 1.5’s million-token context window. I told Gemini to take everything I’d given it and weave together a cohesive daleonai.com blog post on large context windows in my tone and style. The result? You’re reading it.

…is what I would have liked to have said. Actually, the only thing Gemini wrote that I used was that joke:

Overall, Gemini’s output blog post was pretty impressive, but it just wasn’t up to my exacting standards. Did it capture my style? It tried its darndest, using phrases I’ve used before, like: “Hold on to your hats, folks,” and, “So buckle up.” (Cringe! Do I really say those things?) However, Gemini’s output was a bit short. Though Gemini 1.5 can consume long chunks of information, it doesn’t necessarily output long responses. I could have gotten around this limitation by having Gemini output one or two paragraphs at a time, but, well… what can I say? The writer in me wanted to give this post my signature human touch. Maybe I’m too sentimental. Maybe Gemini’s post was better! Who am I to say? You decide.

Regardless, as I was putting this experiment together, I was struck by the feeling that I was toying around with a whole new way of prompting. I didn’t have to do any software engineering to get this blog generator to work. Instead, I spent my time in Google Docs, engineering the perfect word document, one that I could easily reuse in the future by swapping out reference material and form fields. I was truly doing document prompting.

But wait, there’s more

These experiments obviously just scratch the surface of what’s possible with long context windows. Some other experiments that I tried that didn’t make the cut for this post?

- Prompting Gemini with Blake Snyder’s famous Save The Cat screenwriting beat sheet, which enabled Gemini to generate screenplays outlines in Synder’s clever format

- Getting Gemini to analyze hours of GoPro footage, picking out the interesting bits

- Prompting Gemini with a bunch of research papers on medical ailments (i.e. allergies, dry eye) and having it summarize the most SOTA treatments

- Asking Gemini to summarize and simplify the breakthroughs in DeepMind’s Gemini 1.5 research paper

Now I know what you’re thinking: neat, but when am I actually going to get access to Gemini 1.5? I don’t know. I’m sorry. But know that I’m on the edge of my seat too, just waiting to see what awesome things you’ll build.

Comments